Here Dr Claire Bynner, Research Associate at What Works Scotland, shares some of the highlights from the Social Research Association’s annual conference* and discusses how we might bridge the gap between complexity and simplicity, drawing on examples from evaluation research.

In response to a request for a short answer to a policy problem, the stock reply from the researcher is "well….it's more complex than that…."

In his talk at the recent SRA conference, Professor Peter Jackson argued that we need to bridge the gap between policy simplicity and research complexity. He made two suggestions:

This felt like very familiar territory. In What Works Scotland we have been using a collaborative action research methodology to work with four local authorities on public service reform. One of the trickiest stages was right at the start when we were trying to identify knowledge gaps and articulate research questions. The difficulty was how to strike the balance between a topic that is meaningful and relevant to local practitioners without reducing the scope to a narrow instrumental focus that avoids the underlying complexities and dilemmas.

- Policy-makers need to be smarter in the advice they seek from academics - clearer framing of research needs and better understanding of likely outcomes

- Researchers need to be sharper in how we meet the demands of policy - better framed answers and clearer language

This felt like very familiar territory. In What Works Scotland we have been using a collaborative action research methodology to work with four local authorities on public service reform. One of the trickiest stages was right at the start when we were trying to identify knowledge gaps and articulate research questions. The difficulty was how to strike the balance between a topic that is meaningful and relevant to local practitioners without reducing the scope to a narrow instrumental focus that avoids the underlying complexities and dilemmas.

|

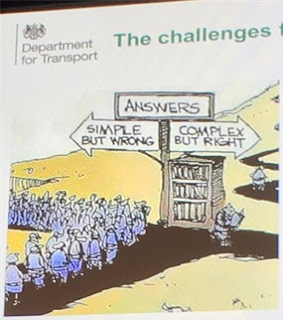

Slide from presentation by Siobhan Campbell from the Department for Transport

|

Siobhan Campbell, Head of the Central Research Team, Deputy Chief Scientific Advisor at the UK Department for Transport, explored the complexity problem further in her presentation on Realist Evaluation.

She asked: How impactful are complex answers? Can researchers help to unravel complexity rather than just describe it? The core of realist and other theory-based evaluations is a process that delves into the black box between the policy intervention and the anticipated outcomes. The purpose is to unravel CMO – Context, Mechanisms and Outcomes. Key to this is the process of developing a theory that can link C->M->O. Through evidence generation, testing and iteration, the theory is constantly refined.

What Works Scotland has used two different theory-based approaches to examine place-based approaches: Evaluability Assessment and Contribution Analysis.

She asked: How impactful are complex answers? Can researchers help to unravel complexity rather than just describe it? The core of realist and other theory-based evaluations is a process that delves into the black box between the policy intervention and the anticipated outcomes. The purpose is to unravel CMO – Context, Mechanisms and Outcomes. Key to this is the process of developing a theory that can link C->M->O. Through evidence generation, testing and iteration, the theory is constantly refined.

What Works Scotland has used two different theory-based approaches to examine place-based approaches: Evaluability Assessment and Contribution Analysis.

In my experience, the evaluation black box can get knocked about quite a bit. Policy evaluations are like the flotsam and jetsam of the policy world. Buffeted about on stormy seas and then left abandoned and washed up on the shoreline. It is not unusual to hear of evaluations where the programme was rolled out before the evaluation had been finished or to hear that the programme was terminated before the evaluation had even begun! In a constantly changing environment the policy agenda can change before you have had time to properly gather and apply the evidence.

Siobhan Campbell identified some other familiar challenges – building evaluation into the policy design, the difficulty of getting the black box theory of change right, the risks of confirmation bias. Getting policy-makers with the right skills who stick around for long enough and who buy in to the need to look at an intervention through a different lens - is really, really hard work. In a world of complexity, there is a greater need to communicate strong and simple messages that can be heard through the maelstrom.

Colleen Souness, Evaluation Officer at the Robertson Trust, argued that successful evaluations change practices and mind-sets. The challenge is to create a culture where people can talk about what is not working (as well as what is). This is obviously more difficult when there is less money and when projects have to compete more for funding. Evaluation for learning requires a safe culture, an institutional drive to evaluate, meaningful and curious questions and space for sense-making and sharing findings. In other words, evaluation can be a tool for learning rather than another form of accountability or performance measurement.

Research and policy work is practised by human beings embedded in social groups. With this in mind Sharon Witherspoon, acting Head of Policy for the Academy of Social Sciences and the Campaign for Social Science, raised some pertinent questions which might be applied to the intergroup relations of researchers and policy-makers:

- Are our groups self sufficient and self referential or do we recognise the characteristics we have in common?

- Can we span simplistic boundaries and cope with complexity?

- How can we behave less like tribes and sects and more like neighbouring communities?

* Claire's attendance at the conference was funded by University of Glasgow's Institute of Health and Wellbeing.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.